Measurement Basics

The attractiveness of chemiluminescence as an analytical tool is the simplicity of detection. The fact that a chemiluminescent process is, by definition, its own light source means that assay methods and the instruments used to perform them need only provide a way to detect light and record the result. Luminometers need consist of only a light-tight sample housing and some type of photodetector. Taken to the extremes of simplicity, photographic or x-ray film or even visual detection can be used.

The simple requirements of chemiluminescent methods make them robust and easy to use. But what about sensitivity?

Chemiluminescence has two built-in advantages here, too.

- Most samples have no 'background' signal, i.e. they do not themselves emit light. No interfering signal limits sensitivity.

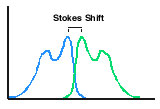

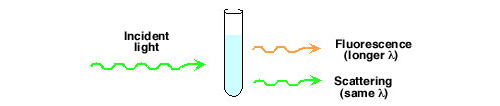

- Measurement of chemiluminescence is not a ratio measurement in the way fluorescence and absorption or color are. In fluorescence this can lead to difficulties with fluorescers with a small Stokes shift. Fluorescence may not be easy to resolve from the exciting wavelength.

Another problem is associated with scattering of the incident light to the detector, especially when samples are somewhat turbid.

The fundamental factor limiting sensitivity in absorption measurement is the need to measure a small difference in two relatively large signals.

Care should be taken to match the spectral response of the detection device to the chemiluminescence spectrum as closely as possible to maximize sensitivity. The photomultiplier tubes commonly found in luminometers show maximum response to blue light and diminished sensitivity to the red end of the spectrum. Solid state detectors typically have better red response.

X-ray film: X-ray film is widely used to record images of chemiluminescent blotting assays performed on nylon, nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes. The user should bear in mind that x-ray film will only detect visible light in the ultraviolet to blue spectral region, although a specialty film with enhanced green sensitivity is available.

Detection in Solution

Some terms are used regularly in the literature and throughout this website in discussing the use of chemiluminescence in assays: sensitivity, linearity, and dynamic range. The meaning of each is described below.

- Sensitivity refers to the lowest level at which something can be reliably detected. That 'something' is typically an analyte to be detected in an assay. The analyte can be labeled with some detectable tag, such as a chemiluminescent compound or an enzyme. The analyte can also be detected by a specific binding reaction with an affinity binding partner having a label. The lowest 'reliable' level at which some signal is said to still be detected, over a blank test sample, is affected by the sample matrix, the nature of the signal compound and the ability of the detector to repeatably sense low levels of signal.

- Linearity describes the relationship of signal to amount of analyte over a range of concentration of analyte. Ideally the proportionality factor should be constant; a plot of signal vs. analyte would be a straight line. Calibration curves deviating from linearity, e.g. s-shaped or sigmoidal curves, can still be useful.

- Dynamic range is the span of concentration of analyte over which signal varies in a monotonic manner with concentration. This defines the working range of the assay - the wider the better in most cases.

What level of sensitivity can be expected from a chemiluminescent assay? The answer, unfortunately, is 'It depends'. Only in rare cases do limitations of detector sensitivity or the chemiluminescence output set a floor to detectability. Modern detectors can sense vanishingly small intensities. Most often other factors contrive to limit assay sensitivity well above levels imposed by the detector. The most common culprit is non-specific binding of biological components (antibodies, enzymes, etc.) to the surfaces of reaction containers and supports. Virtually all immunoassays, blotting assays, nucleic acid hybridization assays and other enzyme-linked binding assays are limited by this effect.

Tubes and Microwell Plates

Glass and transparent or translucent plastic tubes and cuvettes are suitable containers for light measurement. Ideally light should be measured through a flat surface in order to minimize edge effects. Curved surfaces can be used, e.g. through the bottom of a cylindrical test tube. Comparing results taken using different tubes should be made only after determining that the tubes are manufactured uniformly.

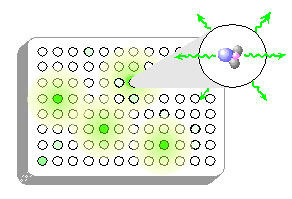

Microwell plates: Light emitted in chemiluminescent reactions is isotropic - it is emitted equally in all directions. If a chemiluminescent assay were conducted in the wells of a transparent microwell plate, light would radiate out not only vertically, in the direction of the detector, but also laterally in the direction of other wells. Light is easily transmitted through the inter-well gaps and through the plate material itself, a phenomenon termed light piping. Relatively bright wells will introduce significant interference in adjacent wells and beyond. For this reason, CHEMILUMINESCENCE SHOULD NEVER BE MEASURED IN CLEAR PLATES.

Microwell plates: Light emitted in chemiluminescent reactions is isotropic - it is emitted equally in all directions. If a chemiluminescent assay were conducted in the wells of a transparent microwell plate, light would radiate out not only vertically, in the direction of the detector, but also laterally in the direction of other wells. Light is easily transmitted through the inter-well gaps and through the plate material itself, a phenomenon termed light piping. Relatively bright wells will introduce significant interference in adjacent wells and beyond. For this reason, CHEMILUMINESCENCE SHOULD NEVER BE MEASURED IN CLEAR PLATES.

Opaque microwell plates and strips are commercially available from several suppliers. They come in two kinds - white and black. Users will notice a significant decrease in signal (approx. 10-fold) using the black plates due to light absorption. Since all wells are affected proportionately, regardless of intensity, quantitation is not compromised. The choice of plate should be based on the expected signal strength, white for dimmer reactions, black for brighter ones. Black plates can also be used to advantage to lessen a non-specific binding background problem.

In addition, all white plates are not equally opaque. White plates designed for fluorescence may have dramatically less white pigment than those designed for chemiluminescence. Fluorescence plates are usually only illuminated one well at a time which eliminates almost all inter-well crosstalk. The opacity of a white microwell plate is easily checked by holding a flashlight against the back of the plate and viewing the wells by eye. Plates exhibiting more than a dim transmission of light may be problematic with strongly chemiluminescent substrates.

Detection on Solid Phase Supports: Blotting Membranes

X-ray film: It has been recognized for several years that chemiluminescent detection of immobilized proteins in western blots and immobilized nucleic acids in Southern and northern blots is a powerful combination. Use of several of Lumigen's chemiluminescent reagents in blotting assays is described in our Product Applications section.

X-ray film: It has been recognized for several years that chemiluminescent detection of immobilized proteins in western blots and immobilized nucleic acids in Southern and northern blots is a powerful combination. Use of several of Lumigen's chemiluminescent reagents in blotting assays is described in our Product Applications section.

Sensitivity is generally more than sufficient for the task at hand, provided that adequate control of non-specific binding is exerted. If not, the power of luminescent reactions typically manifests itself in blackened (overexposed) x-ray films. The best strategy to avoid this problem is to reduce the quantities of binding reagents, i.e. antibodies and the like. Exposure times of 1-10 minutes are usually sufficient to image most blots. Longer times rarely improve signal/background.

O n the opposite side of the sensitivity issue, failure to record signal may not necessarily indicate lack of analyte. Photographic film of any type has a threshold intensity below which photochemical conversion of the silver grains fails. This effect is called reciprocity failure. In practice the result is that chemiluminescent signals below a certain intensity simply fail to register. Longer exposures can not overcome the problem. Methods to combat reciprocity failure include gas-hypering, in which the film is soaked in a mixture of hydrogen and nitrogen gas at elevated temperatures for prolonged periods before exposure and pre-flashing, in which the film is flashed with a short duration low intensity light to raise the photon floor in the photographic grains before exposure to the sample. Neither method is convenient and pre-flashing is difficult to do reproducibly.

n the opposite side of the sensitivity issue, failure to record signal may not necessarily indicate lack of analyte. Photographic film of any type has a threshold intensity below which photochemical conversion of the silver grains fails. This effect is called reciprocity failure. In practice the result is that chemiluminescent signals below a certain intensity simply fail to register. Longer exposures can not overcome the problem. Methods to combat reciprocity failure include gas-hypering, in which the film is soaked in a mixture of hydrogen and nitrogen gas at elevated temperatures for prolonged periods before exposure and pre-flashing, in which the film is flashed with a short duration low intensity light to raise the photon floor in the photographic grains before exposure to the sample. Neither method is convenient and pre-flashing is difficult to do reproducibly.

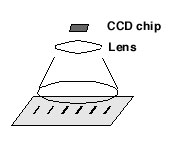

CCD camera imaging: Relatively recently CCD camera systems have become a competitive tool for obtaining and storing images of chemiluminescent blots. These systems can be superior in dynamic range of signal measurement. Response is linear over 3-4 orders of magnitude vs. about 1 order of magnitude for x-ray film. Imaging time is shorter and multiple images can be obtained and stored easily. Although costly up front, their use eliminates the ongoing cost of purchasing film and film processing, not to mention the cost of the processing unit.

Instrumentation: Photomultiplier-Based Detection

Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) have traditionally been the workhorse detector in luminometers. Their advantages include good sensitivity, a broad dynamic range and applicability over a reasonably broad spectral range. PMTs are known for their very low dark currents leading to excellent signal to noise for low intensity samples.

PMT based systems operate in two basic modes, single photon counting and current sensing. There are examples of hybrid systems which are single photon counting to a light level in the low millions of photons/second and then switch to current sensing above that level.

PMT single photon counting systems are capable of exquisite sensitivity. Use of this type of detector is the method of choice for low light detection and quantitation as in, for example, detecting the ultraweak luminescence associated with phagocytosis. The greater sensitivity comes at a cost however. Sample housings must be very light-tight. Moderate light levels saturate the detector; high levels can cause irreversible damage to the PMT.

PMT current sensing systems are also capable of excellent sensitivity and will often read higher light levels than single photon counting systems without damage.

There are differing opinions in the chemiluminescence instrumentation field regarding which system is "better", current sensing or single photon counting. In a modern luminometer, both systems achieve excellent sensitivity and are easy to use. A proper understanding of the characteristics of each system should allow the user to choose the one best suited to the application. We use both types to great advantage and our substrates work well with both.

Solid State Detection

Photodiodes are capable of recording higher light intensities than photomultiplier tube detectors. This facet makes them an excellent choice for applications where high light intensities are to be measured. However, the inherent dark current in solid state detectors is generally much higher than that of photomultiplier tubes. One method of mitigating this problem is to cool the solid state detector via a Peltier or other thermoelectric cooler. Dark currents in solid state detectors drop dramatically with temperatures in the 0 to -30 degree celsius range. Cooled detectors can then be used to integrate the light intensity for one to hundreds of seconds without the signal being overwhelmed by dark current.

CCD and other solid state detectors possess several inherent advantages:

- Solid state detectors typically offer a "flatter" optical response over the visible range. Luminescent reactions emitting red and even near infrared light can be detected with enhanced sensitivity.

- CCD camera systems allow imaging of a variety of objects. Virtually any kind of sample or container can be accommodated ranging from microwell plates and test tubes to bacterial or cell cultures in Petri dishes, electrophoresis gels and blotting membranes.

- Single PMT systems must have the sample position well defined before it can be read. A sample tube has to be brought to a reproducible position to be read repeatably. Microwell plate PMT readers rely upon the standard spacing of microwells and will generally move the plate around to a precalculated position so the wells can be read one by one. Camera systems have the advantage of being able to read a sample without knowing its position in advance, as in the example of a band on a blot. The camera imaging system gives positioning information along with sample intensity.

- CCD camera systems allow imaging of numerous objects simultaneously. In the present era of 96, 384 and higher number well plates, parallel data collection is no longer a luxury. Solid state camera imaging systems have the potential to permit imaging and quantitation of entire plates in one pass.

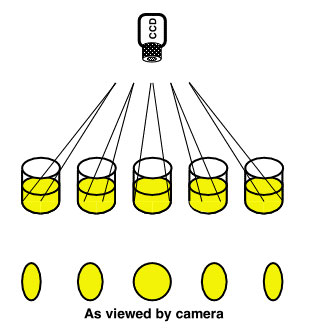

Imaging detectors have a potential serious disadvantage for the quantitation of microwell plates if the instrument designer or end-user is not aware of it. The vignetting problem arises from the 3-dimensional nature of the plate relative to a simple 2-dimensional target, such as a blot. Since light intensity drops off as the reciprocal of the square of the distance to the plate, it would be logical to assume that placing the camera as close to the plate as possible would yield the best result. However, since the well has depth, the entire bottom of the outermost wells might not be visible. This geometric cut-off of part of the emitting well will result in less light being detected coming from the well.

Imaging detectors have a potential serious disadvantage for the quantitation of microwell plates if the instrument designer or end-user is not aware of it. The vignetting problem arises from the 3-dimensional nature of the plate relative to a simple 2-dimensional target, such as a blot. Since light intensity drops off as the reciprocal of the square of the distance to the plate, it would be logical to assume that placing the camera as close to the plate as possible would yield the best result. However, since the well has depth, the entire bottom of the outermost wells might not be visible. This geometric cut-off of part of the emitting well will result in less light being detected coming from the well.

Raising the camera will mitigate the situation somewhat at the expense of a lower overall intensity at the detector. Geometric weighting patterns can be applied to correct for the edge intensity loss, however, the signal to noise ratio for the outer wells must be worse than for the central wells.

Optional Accessories

Most research luminometers and luminometric immunoassay analyzers incorporate a number of highly useful auxiliary components. Sample heaters/coolers and reagent injectors facilitate the chemical processes leading to light production. Components for optical filtering are often provided, while structural features for rejection of stray light such as light baffles and cut-off switches, are mandatory. The benefits of some of the more important accessories are:

- Temperature control: Comparing results within and between days is sometimes confounded by temperature variability in the samples. Particularly in the case of enzyme-catalyzed "glow" type reactions which require several minutes to reach a plateau intensity, temperature fluctuation can lead to changes in measured intensity, detracting from analytical precision. Thermostatted sample blocks and plate heaters can help provide uniform temperatures and permit running reactions at elevated temperatures. The variation of sample intensity can be caused by several effects including the temperature dependent kinetics of the enzymatic reaction or subsequent substrate chemical kinetics. Subtle effects, such as the pH shift of buffers with large temperature coefficients, can cause significant signal variations.

- Monochromators and optical filters allow the isolation of specific wavelengths or ranges. Generally their use is not needed except in specialized applications. Assays and protocols featuring two luminescent species emitting at different regions of the spectra are sometimes used to detect two different analytes. Protocols using a fluorescent acceptor energy transfer compound in conjunction with a chemiluminescent emitter are useful to probe binding processes. Wavelength selectivity comes at a cost though since any device that reduces the range of wavelengths of light reaching the detector inevitably decreases sensitivity by decreasing light throughput.

- Neutral density filters are useful optical elements for extending the range of light intensities measurable by a luminometer by 2-3 orders of magnitude. Consisting of a piece of special grayish glass, and fitting between the sample holder and the detector, these filters function like "sunglasses" to diminish essentially all wavelengths by a known factor. Measured light intensities are corrected to the "true" intensities by applying a correction factor.

- Injectors allow the introduction of substrates or triggers at precise times. This can be important when a kinetically controlled sample has a time varying light curve. Some substrates can be read on the grow-in portion of the curve and will yield accurate results only if all wells or tubes are read at exactly the same time after substrate or trigger introduction. A caveat to injector use arises from the extremely high sensitivity of chemiluminescent measurements. If the injector system becomes contaminated or if different substrate systems are to be used on the same instrument, the injector system can be very difficult to clean thoroughly. Some substrates can detect as little as a few hundred molecules of their trigger agent. Cleaning the pistons, syringe barrels, tubing and valve systems to this level is very difficult without complete disassembly and autoclavability.

References

General discussions of chemiluminescence measurement can be found in these articles.

- J.E. Wampler, Instrumentation: Seeing the Light and Measuring It, in Chemi- and Bioluminescence, J.G. Burr, ed., Marcel Dekker, New York, 1-44 (1985).

- A.K. Campbell, Detection and Quantification of Chemiluminescence, in Chemiluminescence Principles and Applications in Biology and Medicine, Ellis Horwood, Chichester, 68-126 (1988).

- F. Berthold, Instrumentation for Chemiluminescence Immunoassays, in Luminescence Immunoassay and Molecular Applications, K. Van Dyke and R. Van Dyke, eds., CRC Press, Boca Raton, 11-25 (1990).

- T. Nieman, Chemiluminescence: Theory and Instrumentation, Overview, in Encyclopedia of Analytical Science, Academic Press, Orlando, 608-613 (1995).